Masks of the members of Pink Floyd on display in the exhibition Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains at the V&A.

The Victoria & Albert Museum in London can hardly be faulted for experimenting with new forms of exhibitions. Museums worldwide have been seeking new ways to engage with visitors for decades in an attempt to avert whatever crisis museums feel they are currently embroiled in, and technological innovation is usually a sure-fire path to surging visitor numbers.

Beginning with the David Bowie Is… exhibition of 2013 (now on tour), the V&A have partnered with audio company Sennheiser to produce a series of blockbuster exhibitions based around the act of listening to popular music, including two exhibitions that I have recently visited: You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970 (which ran from 10 September 2016 to 26 February 2017) and Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains (currently on view until 1 October 2017). Using a proprietary technology developed by Sennheiser, visitors wear a lanyard attached to a receiving unit, into which is plugged a pair of Sennheiser headphones. The receiving unit picks up broadcast signals inside the exhibition galleries based on the wearer’s location, pushing audio content to the visitor based on a series of proximity sensors – in theory, wherever you stand, you’ll be listening to audio associated with what you’re looking at. It’s an intriguing premise, not unlike the way audio is delivered at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. In the case of the Revolution exhibition, the sounds pushed to the headphones included reconstructed historical soundscapes of neighbourhoods in 1960s London that were meant to interact with other sounds being played over speakers in the galleries; the Pink Floyd exhibition’s galleries remain silent until the end of the show, when visitors are ushered into a video theatre meant to evoke the experience of sitting on the grass at an outdoor music festival, the same technique that was also employed in the Revolution exhibition.The trouble is, Sennheiser’s technology simply does not work.

My experience of the audio delivery system at both exhibitions was incredibly frustrating and not immersive in the least due to its consistent technical difficulties. Very often the sound did not sync up with where I was standing, and I would eventually figure out it was matched to a video displayed on the other side of the room, or in a different room entirely. This happened at both shows, multiple times – and I made sure to walk at varying speeds to see if it was something to do with my own own pace or movements.

The streaming sound is high quality when it works. However, it has a tendency to glitch and buffer frequently, to the point where more than 90% of the time I was in the Pink Floyd exhibition, whenever I would hear a song I liked and wanted to hear more of, it would either buffer, skip, or stop entirely just as I was getting into it.

The only area where the sound system worked flawlessly for me was, luckily, in what is the most museologically successful area of the exhibition as well in terms of visitor experience: an interactive mixing board gallery, where visitors can try their hand at one of several duplicate mixing boards to work the faders on the main audio tracks of Pink Floyd’s mega-hit song ‘Money’ from their 1973 album Dark Side of the Moon. Here, more than likely due to the need to stand still, the sound was crystal clear and glitch-free, providing visitors with a reasonable approximation of what it feels like to mix music in a recording studio via one of Pink Floyd’s most recognisable songs – and who wouldn’t be excited to be able to manipulate a fader on a mixer marked ‘CASH REGISTER’? However, as I stepped away from the mixer and made my way across the room to watch one of the videos on display, it took more than a minute for the audio to switch over from the mixing desk area to the documentary video – which meant I was treated to a young boy’s rapid-fire Money remix while watching David Gilmour’s lips move for an uncomfortably long time.

Having experienced an inordinate amount of glitches at the Revolution exhibition, I thought that perhaps it was my own fault since I attended that show in its final week, during a peak afternoon time slot which was massively over-crowded, so I assumed the technical problems were due to there being too many requests on the network. So when attending the Pink Floyd exhibition earlier this week, I made sure to arrive at opening time on a weekday when it was relatively quiet, not too close to the show’s premiere day and far enough in advance of its closing date to make sure the audience levels would be sparse, which they were. I also wasn’t running a personal hotspot from my phone (which visitors are warned can interfere with the functionality of the headsets via a sign posted next to the exhibition’s entrance). I can only conclude that I had a pretty typical experience after the same thing happened to me twice in two exhibitions with completely different numbers of visitors using the system each time.

Aside from the technological disappointments, a brief note must be made about the logistics of headphone-based exhibitions. Never mind that forcing everyone to wear headphones makes for a socially isolating experience in a gallery space, but the combination of ambulatory headphones and exhibition spaces are not necessarily a match made in heaven, particularly when the vast majority of people in a crowded exhibition space are baby boomers unused to navigating the world while not being able to listen to their surroundings. People simply forget how to wayfind while wearing headphones, and lose awareness of the fact that they are not alone in the gallery space: they back into each other when trying to get a better view or take a picture, rapidly change their mind about where they want to go, and end up unexpectedly clotheslining someone else. I witnessed so many collisions and near disasters during both of these shows, I can only imagine how much of a nightmare it must be for the Gallery Attendants to manage.

From a museological perspective, I also found both shows disappointing. Obviously, the combination of museums and the world of rock music is going to produce certain tensions – case in point, the museum-friendly yet decidedly un-rock-and-roll presence of signs that say Please do not lean on the walls inside the replica outdoor festival concert space at the end of both exhibitions. However, beyond these admittedly entertaining tensions, both shows were fraught with curatorial problems.Revolution’s curation was in desperate need of editing; it simply had too much content and overwrought design to effectively communicate its messages, and added to traffic flow issues – see the photo above of the concert space from Revolutions, the perimeter of which was surrounded by displays of costumes and instruments. There were also some crucially disappointing curatorial choices, particularly in what was the exhibition’s ‘big finish’. Revolutions closed with a video of ‘current events’ clips bringing the visitor up to the present day, illustrating how the counterculture of the 1960s has either had an impact upon or been completely obliterated from the present – a good idea made tedious by the video’s excessive duration (particularly coming at the end of the massive overdose of visual and textual information that was the Revolution exhibition, this video almost felt like a form of punishment). Most significantly, however, immediately following the video, the visitor was presented with the final object in the exhibition, meant to inspire a sense of hope: the handwritten lyrics of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Imagine. This was a powerful, positive, thought-provoking message to end upon – except the object on display is a photocopy, framed like an original; perhaps a fitting museological metaphor for the end of countercultural idealism, but inherently disappointing when one is standing inside one of the world’s most highly-regarded museums in a city nearly synonymous with The Beatles.

The Pink Floyd exhibition is, according to the show’s marketing materials, ‘Presented by Pink Floyd, The V&A, and Iconic Entertainment Studios.’ This information is extremely significant when considering the show’s curatorial voice, which borders on the hyperbolic and the post-factual. The first didactic panel that greets the audience begins:

‘Pink Floyd are one of the greatest bands in the history of music.’

This sets the tone for a show that is entirely uncritical of its subject, a show that glosses over both the exit of original lead songwriter Syd Barrett and the band’s long-term court cases against each other to portray them in a glowing light as untainted, god-like musical innovators. Looking back at who the exhibition is ‘presented by’, the first of the three presenters is the band itself (who, as a juggernaut within the pop world, employs its own marketing team); followed by the V&A; then rounded out by a third entity, Iconic Entertainment Studios, an organisation also responsible for such events as the doomed Broadway musical Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark, Transformers Live!, and An Evening With Oprah. Revolution’s parting message about the counterculture’s loss of innocence and subsequent sublimation by neoliberal ideals couldn’t be clearer.

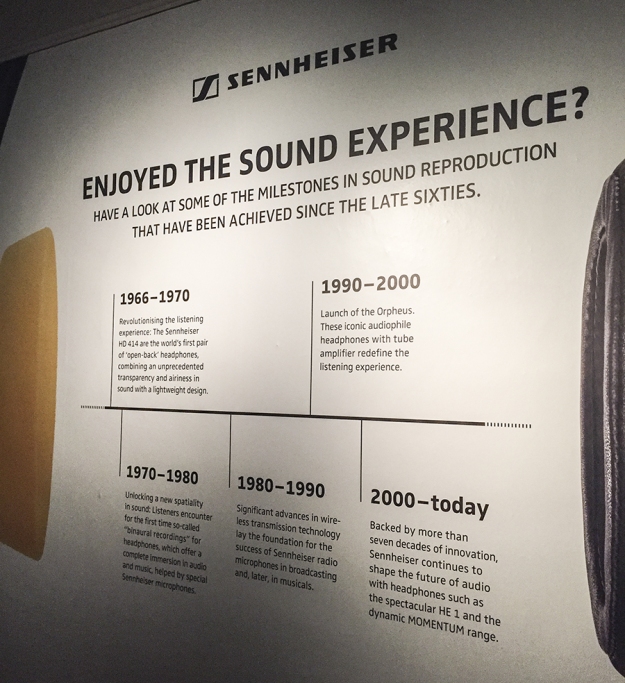

So perhaps the fact that these museum exhibitions about music use a sound system that makes it difficult to actually enjoy listening to the music starts to make more sense upon further thought: in a post-factual world, who cares if the technology you just used to listen to this awesome music you grew up with actually works or not? You’re in the presence of greatness, looking at Roger Waters’ guitar, and you’ve heard Another Brick In The Wall (Part 2) a million times anyway, so who really cares if it skips a couple times here in the V&A? But then, in a move of utter crassness, these blockbuster exhibitions go ahead and reveal that they are just as interested in promoting Sennheiser’s products – the same products that did merely an okay job at delivering audio content to you minutes before – as they are in presenting the actual exhibition subject matter. For example, at the exit of the Revolution show, the audience was presented with a display (seen below) that blurred the line between museological authority and corporate interests – a timeline of ‘milestones in sound reproduction since the late sixties’ that, when you read the fine print, only focuses on Sennheiser’s product lines. This quite simply damages whatever faith the audience may have had in the unbiased institutional authority of the V&A before they attended the exhibition.

Sennheiser-centric ‘Milestones in sound reproduction’ didactic at the end of the Revolutions exhibition.

All of this being said, Sennheiser’s ‘Sound Experience’ system simply isn’t capable of delivering what it sets out to do. Seeing the historical artefacts on display (when they aren’t reproductions) is one thing, but if I want to listen to Pink Floyd buffering, I can do that anywhere, anytime with Spotify.